Interview Series: Bison Rancher and Owner Rex Moore of Rock River Ranches

This article is shortened from a chat that I had with Rex Moore, the owner of Rock River Ranches, a local bison rancher in the Denver, Colorado, area. We dove into his early ranching beginnings in Idaho, raising a rare breed of French cattle, Salers (pronounced “Sa-Lairs”), and later transitioning to bison. Like the bison who run into a storm to face the challenge head on, Rex is as resilient. Losing 80% of his business in one week due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, he quickly rebounded. Through a social media post that went viral, compassion from the American people came to his service. In 24 hours he had 1,000 orders which saved his business. Today, better than ever, Rex is serving the highest quality, nutritious bison meat to restaurants and individual Americans in all 50 states.

If you prefer listening instead, the full-length interview is at the link below:

Rex, it’s great to talk to you today. To start off, I’m curious where you are originally from and a little bit about your family?

I'm a fourth-generation livestock producer, going back into the late 1800s. In 1972, my father bought a ranch that fronted the Snake River, just outside of Weiser, Idaho. My father is one of the American founders of the Salers breed of cattle from south-central France.

The first full blooded Salers bull that came to the United States from France was genetically unique. Because of the [genetic] superiority in the Salers cattle, it eventually became the eighth largest breed in the United States. So, we started a company called Maverick Ranch Association in 1986, right when I was graduating from college. We started here in Denver to be centrally located. We used to start supplying these naturally raised [cattle] with no antibiotics, no growth hormones from animals to grocery stores. In the mid-1980s, that was kind of the beginning of natural beef, which also evolved into organic beef as well.

We started Maverick Ranch and eventually grew to a company in a processing plant that we had here in Denver. We had 275 employees, we supplied beef to over 2,000 supermarkets in the in the U.S.

You mentioned how you went from Idaho to Denver. Is that because it’s a good distribution hub, centrally located to get the product to the market easier?

My father graduated from Colorado State University and my mother graduated from CU. So it was kind of like coming back. Denver was good place to start a new business. Centrally located for shipping product to grocery stores all over the United States. Idaho was a little isolated in the 1980s.

How did raising Bison come into your life and were you exposed to that at an early age? Or was this kind of something later, you discovered?

My father was walking through an auction in the 1980s and bison were selling cheaper than the Salers cattle and he's like, oh, I should have some of those. My father should have been born in the 1700s because he’s kind of like from that era. We had a hunting and fishing lodge on our ranch called the Mountain Man Lodge and a marina that he built all around the mountain man theme. So every mountain man place ought to have some bison running around.

In 2009, because of the bad economy, we were carrying too much debt and forced to close the business. We lost the ranch in Idaho to the bank and had to do something new. So I told my brothers that we should sell bison meat to local restaurants here in the Front Range [Wyoming-Colorado region]. In 2016, I bought my own herd in Cody, Wyoming and moved it to the edge of Kansas, in Wray, Colorado. I harvest over 200 bison a year for my restaurants. I also buy some from other Colorado producers.

During that time period, I also started selling hearts, livers, kidneys, tongues, bones to various animal food companies. So there's a portion of my business that I buy other people's bison organ meats and bones and turn around and resell them. And today that's probably about a third of my total business.

Was your business affected by the recent COVID-19 Pandemic?

In 2020, March specifically, about the 18th [when] COVID hit, I lost 80% of my business in one week. And was devastated. And so I posted on Facebook and I had less than 100 people that even knew who I was on my personal [account]. I had no website. I posted to those 100 people. They started sharing everywhere.

So, the Rock River Ranches website was only made just three years ago?

It was built but not operational. Within five hours those 100 people had shared my post, my plea to America 12,000 times. By the next morning, it had been shared 24,000 times. I was like, okay, what do I do? So my wife creates an order form online and we had my personal phone and email in there. I took 1,000 orders in the first 24 hours. There was a meat shortage. Grocery stores were running out of food.

Were people ordering from all over the country? And was it mostly individuals or restaurants?

No, it was all private individuals, then the news media got a hold of it. I was interviewed by three television stations, a radio station, there were newspaper articles being written because they wanted to share the story of how America was rallying behind me. In some of those interviews, I got very emotional. I never missed a day at work. I worked 12 weeks in a row, seven days a week, doing local deliveries.

As a way of saying thank you to the American consumer, I keep selling direct to consumer, I can ship anywhere in the United States in a few days. So right now, if you want a side (1/2 of the animal) or quarter of a whole bison, I can have it ready for you in two days.

Wow, there's really no wait time?

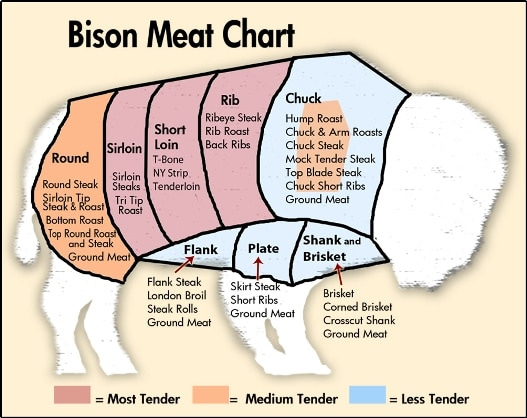

Typically, if you get an animal harvested for a side (1/2 of the bison) or quarter, it takes a year to book a date, and in some cases, it was almost two years during COVID because people couldn't buy meat at the grocery store. So they wanted to try to buying direct from the farmer and the rancher. And so I have burgers, steaks, roasts. I sell raw sausages like chorizo and Italian and breakfast sausage. I have cooked sausage links. I have cooked corn brisket. I have a New England style black pastrami.

I use almost the whole animal, and I take as many of the organ meats and even bones [as possible]. I'm starting to use 85% of the weight of the carcass of the animal. Just like Native Americans did. I'll cut up liver and heart so you don’t have to buy a liver or a whole heart.

What's your favorite kind of thing to make or cut of bison?

One of my favorites is a bison prime rib. That's always fantastic. However, one of the top-notch items we make is a 100% bison Italian sausage. Also ground bison in one-pound packages. We won't eat spaghetti anymore in our house without bison and so that's always a family favorite. So it's just a lot of different kinds. But you know, I do enjoy a good [bison] steak.

What would you say is the most popular cut that people buy, like top selling?

By volume, the ground bison. We sell it both in one-pound packages and five-pound packages. We do sell an awful lot of what we call middle meats or the steak meats. New York strips, filet mignons. It really just depends. And we've got steak bundles and roast bundles. We have a big sampler pack if you want to just be able to sample a bunch of different things for what you like. There’s a whole variety.

Why do you think people come to buy bison from you?

One, people like the taste and flavor and the leanness of the product. A little bit health conscious. There are a number of people that are allergic to eating beef. Yet they can eat bison just fine. We've had people switch because of COVID and starting to buy from us. That's the only meat they buy is bison from Rock River Ranches.

Here's an interesting thing. Let's say in the 1920s, there was somewhere around 3,500 bison left in the world. And because of ranchers and farmers, they were saved. Today there are over 450,000 bison in North America. There's a program called Bison 1 Million and we're trying to get bison back to 1 million head. If you eat bison, you save bison. The more bison meat we sell and eat, the more ranchers will start raising them. It’s quite interesting because of a lot of ways, it’s easier to raise bison than it is beef.

Oh, really? So wondering about that actually, how do bison and cattle compare to each other?

You're not going to worry about your bison in a storm. A bison can eat snow, they don't have to have the water trough cracked open in the morning. A bison faces a storm directly into the wind. Cattle will run away, and then they'll get stuck in fences. Bison just love the cold, and they can handle the snow perfect. And the cold temperatures, they actually do better in the northern half of the United States and Canada, because of all the hair that they have on them.

They're very smart, and they're very trainable. And so they like alfalfa cubes. And you can shake a bag of alfalfa cubes, and they'll come running for a half a mile away to come get those alfalfa cubes. And then you lead them into the next pasture. You'll never have to chase a bison.

They're still semi-wild. And if they have feed in their pasture, they're fine. But if they run out of feed, they're leaving. A big bull can jump flat footed, over a six-foot-tall fence. They aren’t bothered as long as they have grass, but if they run out, they're leaving town.

I have bison that are 15, 16 years old, that are still calving and they can make it into their 30s. Usually if they get that old, they're not having as many calves but the average age of a beef animal is maybe nine years old.

How much do bison cost to raise compared to cattle?

About the same [as cattle], you're going to spend more on capital expenditures upfront such as cattle chutes and your handling facilities such as corrals.

How do bison handle stress?

Bison can't handle stress very well. And so you try to not stress them out in any of your animal handling practices. We don't use whips, we use flags to move them. Oh, and we don't use hot-shots. We do more of a low stress handling system. Bison just naturally are somewhat semi-wild still. They're not truly domesticated.

And so, you can stress out on animals to the point that they will die.

And typically an injured bison doesn't survive very long either due to stress. I've seen people try to give antibiotics to an animal that had a broken leg or a bad cut, you know, and yeah, they won't make that overnight.

You're never gonna go out into a herd and shoot an animal. Because they will get upset.

Are they easier to raise than cattle?

For the most part, it's easier to raise bison, except that one time of year that you got to work on and wean the calves, and give them their tag numbers and their identity. We do use electronic ear tags for traceability as well as visual tags.

And so, a lot of animal husbandry practices are the same. But you know, the shoots are massive. They have this big head, a lot of people use hydraulic chutes instead of manual shoots. And so you spend more in capital expenditures on some of your fencing and some of your equipment.

What do you enjoy the most about raising bison?

I think it's probably twofold. One, I'm helping bring back the U.S.’ national mammal that was almost extinct. Second, I think the enjoyment. In my restaurant customers, the end user, the person that sits down and says, “Oh my god, that was amazing.” I was in one of my restaurants that's been serving bison for almost five years now.

Which restaurant is that?

It's called Duo in the highlands. And here in Denver. They ran out of product, New Year's Day.

They're like, we had somebody come in on the second. And we were out of product. It was four people, and they all wanted bison. And we were out. They all got up and left the restaurant. They didn't even order drinks.

People rave about the quality of bison product that are sold at these restaurants, to listen to my consumers that say, oh my god your stuff’s amazing Rex. We won't eat anything else at home.

That's where I get my satisfaction.

Why bison instead of beef?

The bison market is way more consistent. It doesn't have the ups and downs of the beef industry, the beef industry cycles, sometimes every five to seven years. The bison cycles much closer to 12 maybe even 15 years.

Now let's compare the size of the industry. In the bison world, we harvest 65,000 head a year in the United States. Okay, 65,000 sounds like a lot. But in the beef world, they harvest 600,000 a week. So, you know, you have lots and lots of plants that can do 10,000 heads a day.

It’s big corporate America. And then the bison. Even if we get to bison 1 million. We cannot supply one bison burger for every man, woman and child in the United States one time a year.

So the market potentially is huge.

People usually try bison, they like bison, they start buying it.

And they become a regular consumer. One time I tried to sell ostrich meat. People try it once and they’re like, I don’t think I need that again.

What are some ways to grow the bison industry?

We need to expose more people to bison. So, for the last two years, we have something called Colorado Proud Day, which is featuring locally raised Colorado foods, in schools.

7,000 students in the Boulder Valley School District have got to eat a bison burger.

So kids growing up will say to their parents, I had a bison burger at school today. Now they might try one down the road later in life. So over the last five years, I've supplied three or four different school districts.

The more people will try it, the more people will eat it. The more ranchers that raise it, the more bison there’ll be in North America, and then I don't know when we're going to hit Bison 1 Million.

But to think about it, if we looked back, I don't know. 500 years ago, there was 60 million head of bison. That's how many - hard to believe - that's how many cattle are in the United States. In both beef and the dairy world, it might even be more than that. So yeah, I mean, 60 million versus 450,000. Let's just get to 1 million.

Are bison burgers usually less fat?

Typically all my bison burgers are 90% Lean. There's just a lot of interest and intrigue and as more people learn about it, they try it.

For your bison meats, have you shipped all across the country or mostly Colorado?

I've shipped bison to Alaska and Hawaii. So, I've shipped to every state.

I just had one last question, why don’t bison require USDA inspection, why is it just voluntary?

As the American government created the USDA, they turned over meat inspection to them. It’s for your primary proteins: beef, pork, lamb, chicken, turkey. But there were what we call game animals. Elk, venison, bison, rabbits, and other game birds all fall under something called voluntary inspection or what we call the triangle.

So, if you see a USDA triangle, it's gone through USDA inspection. If it's got a circle, it's one of the other proteins.

But it's voluntary. You pay extra for it.

Some of my items carry the triangle, and some don't, it just depends on what part of the process and what part of the animal you got. All of my bison meat is processed in a USDA facility. But when I go to make steaks and sausages and things like that, it's not necessary, and my restaurants don't care.

Have you had to deal with any shipments to customers arriving late?

Last year, I think I only had one delivery late.

Basically, we ship everything with one day's buffer. And we have enough dry ice and we know what our cooler capacity is. That even if it is one day late, it's still frozen.

Are there are other states that order more than others, or is it just kind of all across the country?

All over. I have some people that order once a year, around 20 or 30 pounds. Now they're buying sides and quarters, getting 150 to 250 pounds. We have customers that buy every single month.

We also have cooking videos, and recipes. And we send free spices with our product as a thank you.

I want to do a cooking video on something called chilled tenderloin. Growing up, we always did chilled tenderloin for a party, because you've cooked it the day before and you serve it chilled. You don't have to worry about cooking that day for your party already.

Is there anything else I may have missed that you wanted to mention?

This covers a lot of the good story.

But yeah, just hearing about how you got started in bison going back with your dad and it just seems so neat. All the stories. How bison are resilient. It kind of speaks to yourself a lot too, after 2009…the Great Recession and then COVID.

That concludes the interview with Rex Moore. I hope that you all enjoyed this interview as much as I did. If you would like to learn more about Rock River Ranches or support Rex and eat those tasty bison meats from one of Colorado’s finest bison ranchers, drop Rex a visit at his website!

👉If you enjoyed this post, feel free to share it with friends!

Related Articles: